MENU

Starting a Business

- Best Small Business Loans

- Best Business Internet Service

- Best Online Payroll Service

- Best Business Phone Systems

Our Top Picks

- OnPay Payroll Review

- ADP Payroll Review

- Ooma Office Review

- RingCentral Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Finance

- Best Accounting Software

- Best Merchant Services Providers

- Best Credit Card Processors

- Best Mobile Credit Card Processors

Our Top Picks

- Clover Review

- Merchant One Review

- QuickBooks Online Review

- Xero Accounting Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

- Accounting

- Finances

- Financial Solutions

- Funding

Explore More

Human Resources

- Best Human Resources Outsourcing Services

- Best Time and Attendance Software

- Best PEO Services

- Best Business Employee Retirement Plans

Our Top Picks

- Bambee Review

- Rippling HR Software Review

- TriNet Review

- Gusto Payroll Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

- Employees

- HR Solutions

- Hiring

- Managing

Explore More

Marketing and Sales

- Best Text Message Marketing Services

- Best CRM Software

- Best Email Marketing Services

- Best Website Builders

Our Top Picks

- Textedly Review

- Salesforce Review

- EZ Texting Review

- Textline Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Technology

- Best GPS Fleet Management Software

- Best POS Systems

- Best Employee Monitoring Software

- Best Document Management Software

Our Top Picks

- Verizon Connect Fleet GPS Review

- Zoom Review

- Samsara Review

- Zoho CRM Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Business Basics

- 4 Simple Steps to Valuing Your Small Business

- How to Write a Business Growth Plan

- 12 Business Skills You Need to Master

- How to Start a One-Person Business

Our Top Picks

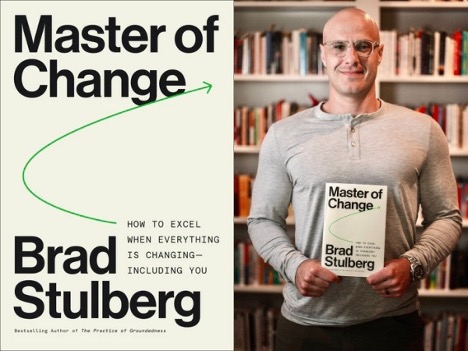

Master of Change Author Brad Stulberg Wants You to Learn “Rugged Flexibility”

The average person experiences a “disorder event” every 18 months, according to Brad Stulberg, author of recent bestseller Master of Change: How to Excel When Everything Is Changing — Including You. These include starting (or losing) a job, entering (or ending) a relationship, moving to a new city, having a child, and other life inflection points.

So, how do we foster a sense of resilience in the face of inevitable professional and personal disruption? Stulberg spoke with b. about his concept of “rugged flexibility.”

b.: Aren’t “rugged” and “flexible” basically opposites?

Stulberg: So most people … think that these are diametrically opposed opposites. To be rugged is to be tough, durable, determined; to be flexible is to be soft, supple, bend easily without breaking.

And what I found … is that individuals and organizations that sustain excellence over the long haul — and navigate periods of change and chaos and disorder, and even just the inevitable ups and downs — they’re not rugged or flexible. They’re rugged and flexible. They take these two competing ideas and they’re able to practice them and hold them at the same time.

Ruggedness generally comes from a sense of one’s core values or key strengths — what really makes them who they are. This could be as an individual, but it could also be as an organization. And then the flexibility component is, over time, how do you take those strengths and apply them in new and creative ways when the circumstances change?

And it’s really the fundamental principle of evolution, of growing through change. It is figuring out what makes you who you are and then being able to adapt on everything else.

b.: What can companies do to empower their employees to practice this kind of mentality?

Stulberg: Have a good sense of what their core values are — what they really stand for — but then separate those core values from actual behaviors and practices.

So, if a company’s mission is to deliver lifesaving treatments to individuals with a certain disease, that’s the core value. But how they do it and how they practice that ought to change as technology changes. If a company’s core value is to be a really entertaining media company, that’s the core value. Well, is that through television? Is that through podcasting? Is that through YouTube? Is that through TikTok?

Empower the organization and employees to be really creative in how they accomplish that value and to adapt the practices and behaviors over time. … Help employees gain a sense of their own personal ruggedness. So what are the traits that really make them who they are? What are their strengths that they might want to double down on?

And then help them understand that — when they’re faced with ambiguity or change or uncertainty — they can go back to the strengths and they can ask themselves, “Well, how might I apply authenticity?” or “How might I apply kindness?” or “ What would the creative thing to do be?”

b.: How do you identify those core values?

Stulberg: Imagine that you’re older and you’re looking back on current you. What would older you be proud of? Another way into core values is to think of someone whom you really admire and then ask yourself, “What do you admire about that person?”

Research shows that you want to try to get it to three to five [values]. Anything more than that, it’s very hard to actually have it be core — and anything less, you maybe become a little too unidimensional. … Core values really become like an internal dashboard in the sense that if you take the actions that align with them, you feel good. Whereas the more that your actions stray from your core values, the worse you tend to feel.

b.: You talk about “having mode” and “being mode.” How do those concepts relate?

Stulberg: “Being mode” is when you identify with your fundamental motivators and drivers. “Having mode” is when you identify with what you have. … And how this helps in periods of change is, the things that we have, they’re often taken away [and] our sense of identity and self-worth gets really fragile. You end up in situations where maybe you start engaging in unethical behavior to hold on to those things. Lance Armstrong and Elizabeth Holmes are two people that operated in “having mode.”

Now it’s not to say that we’re gonna completely release from it. I mean, we all are status-seeking creatures — it’s just part of homo sapiens being human. So I think the work is really just trying to shift [to] the “having” characteristics.

Maybe you make a ton of money and you’re a phenomenal investor and you have a really nice house. So that’s having, but the being characteristic underneath could be problem-solving or curiosity. Identifying with those things more than what you get as a result.

Another way to think about it is process versus outcome: Identify the process of striving for what you want, and let the outcomes fall where they fall. … Whereas if you latch on too closely to the outcome, then you can see how — especially when the outcomes start to shift negative — it is really disorienting and it can feel like an attack on your sense of self.

If you’re an entrepreneur, you need to expect it to be hard. If you go into it thinking it’s 100,000 Twitter followers and a private jet and a unicorn company, you’re just going to be perpetually miserable. You’ve got to expect that it’s going to be a grind. It’s going to be chaotic. There’s going to be change all the time. And if that’s your expectation, then you have a chance of meeting the moment.

Meaning you’ve got to be kind to yourself and you’ve got to have your own back. Because if you can’t … then you’re never going to be willing to fail. Or if, when you do fail, you beat yourself up. You’re just not going to last. So it’s this other paradox, which is that fierce self-discipline really requires fierce self-compassion.

b.: We’ve seen a lot of economic upheaval in huge sectors: tech, entertainment, hospitality, media. How can employees facing this practice both “wise hope” and “wise action,” as you put it?

Stulberg: What tends to happen out in the media is you get these two extremes.

The one extreme, I’m going to call it “toxic positivity,” which is just “have a good attitude [and] everything that you wish for will come your way.” And that’s utter bulls*** most of the time. The other extreme is nihilism, despair, “everything is so broken,” “the structural forces are so great,” “there’s nothing I can even try.” You know, “Screw the system; bring it all down.”

And, even though they seem like opposites, both those extremes have one thing in common: It absolves you of needing to do anything. … The job of being a mature adult — or a leader, especially — is to always make sure you’re existing somewhere in the middle and accept the inevitable hardships and see reality clearly for what it is without losing hope that you have some agency and the actions that you take can affect the situation.

“Wise hope” and “wise action” is in these situations. It’s about figuring out what you can control from what you can’t — separating those two things — and then trying to focus on what you can control.

In the literature, it’s called “behavioral activation.” The shorthand is that you don’t need to feel good to get going. Sometimes you just need to get going to give yourself a chance at feeling good. … Right action generally leads to right thinking.

b.: Do you have a morning routine that helps get you into the zone?

Stulberg: Yeah. I used to have more [rituals] and then I had kids. So my morning routine now is, just make a pot of coffee, and it’s really — that’s it.

We get the kids out the door to school, so on and so forth. But if, before I check my phone, I can just make a pot of coffee and smell the coffee and just go through that, that is good.

But I also have gotten really good at writing while walking the dog. Meaning I have six ideas for subheadings and I just make a voice note in my phone [or] capture it in a notebook. So, in a way, I’m always writing. And then it’s really just about finding the time to sit down and put it together.

Master of Change is available now.

This article first appeared in the b. Newsletter. Subscribe now!