MENU

Starting a Business

- Best Small Business Loans

- Best Business Internet Service

- Best Online Payroll Service

- Best Business Phone Systems

Our Top Picks

- OnPay Payroll Review

- ADP Payroll Review

- Ooma Office Review

- RingCentral Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Finance

- Best Accounting Software

- Best Merchant Services Providers

- Best Credit Card Processors

- Best Mobile Credit Card Processors

Our Top Picks

- Clover Review

- Merchant One Review

- QuickBooks Online Review

- Xero Accounting Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

- Accounting

- Finances

- Financial Solutions

- Funding

Explore More

Human Resources

- Best Human Resources Outsourcing Services

- Best Time and Attendance Software

- Best PEO Services

- Best Business Employee Retirement Plans

Our Top Picks

- Bambee Review

- Rippling HR Software Review

- TriNet Review

- Gusto Payroll Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

- Employees

- HR Solutions

- Hiring

- Managing

Explore More

Marketing and Sales

- Best Text Message Marketing Services

- Best CRM Software

- Best Email Marketing Services

- Best Website Builders

Our Top Picks

- Textedly Review

- Salesforce Review

- EZ Texting Review

- Textline Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Technology

- Best GPS Fleet Management Software

- Best POS Systems

- Best Employee Monitoring Software

- Best Document Management Software

Our Top Picks

- Verizon Connect Fleet GPS Review

- Zoom Review

- Samsara Review

- Zoho CRM Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Business Basics

- 4 Simple Steps to Valuing Your Small Business

- How to Write a Business Growth Plan

- 12 Business Skills You Need to Master

- How to Start a One-Person Business

Our Top Picks

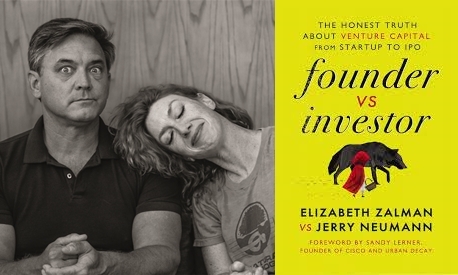

Founder vs. Investor: A Playbook for Getting Capital and Not Losing Your Company

Table of Contents

Founders don’t want to yield control. Investors don’t want to open their wallets with no strings attached. So, does the relationship need to be a battle of wills?

Not at all, according to entrepreneur Elizabeth Joy Zalman and venture capitalist Jerry Neumann, coauthors of Founder vs. Investor: The Honest Truth About Venture Capital From Startup to IPO. It’s simultaneously a guide for founders (so they don’t get ousted by their board of directors) and for investors (so they don’t smother visionary brilliance).

Zalman and Neumann told b. how the two sides can solve mutual problems by better understanding each other.

b.: What sparked the idea for this book?

Neumann: About two years ago, one of the founders I invested in was fired by the board of directors. And I was frustrated because I felt the founder had been doing a good job, and it was more a reflection of internal politics than on the founder himself. I took my frustration and wrote a blog post. My blog is usually read by other venture capitalists. It’s an exploration of deep topics in venture capital. This post was, instead, based on an email I had been using to founders that talked about how to deal with your board of directors once you have venture capitalists on.

It really took off … I realized the people who were reading it weren’t venture capitalists, but were founders. It seemed to really have struck a nerve. It was called, “Your Board of Directors Is Probably Going to Fire You.” In retrospect, it was something of a provocative title. But it’s a fact that most founders of venture-backed companies, the majority of them, end up getting fired. The idea was: How do you deal with your board in a way that won’t get you fired?

Liz called me and said, “Why isn’t there more of this? Why don’t more venture capitalists write about this?” We decided to write this book, which would explain why investors do the things they do. She would write about how the relationship looks from the side of the founder. It’s something that’s been under-talked about in the VC world, this idea of how people deal with each other.

b.: How can investors and founders work together to make the relationship less adversarial?

Neumann: We’re not trying to get rid of the places where founders and investors fight — because we really can’t. The whole point in writing this book and having two voices in it was to get away from the typical business book idea of giving people solutions. We’re not saying, “Here’s a solution so boards and directors and founders will never fight with each other.” That will always happen. But if you know it’s going to happen, and you know why it’s going to happen, you can work through it and work with it.

Zalman: Here is the crux of the problem from the founder perspective: “I don’t understand enough. I don’t understand what I need to. And I’m not knowledgeable enough to make a strong, strategic decision for me and for my company.” This book helps both sides understand why people do the things that they do.

But to go back to your question: The answer is pause, and breathe, and diligence. Pick up the phone. Ask questions.

b.: What’s a big problem that founders and investors should anticipate?

Neumann: Both sides feel like when they say things that aren’t necessarily 100% true, it’s an acceptable sales tactic. And when the other side says it, they just believe it. Founders will say, “We’re going to be a billion-dollar company in three years.” … And VCs will say, “We’re going to be there every day helping you pack boxes and putting shipping labels on them.”

Not literally, but you know what I mean. And, founders take them at their word that they’re going to do that. And, of course, VCs don’t do that. They’re not good at that! That leads to people being disappointed on both sides.

Zalman: I will add that it’s important for founders to understand why VCs are giving them money. Investors are placing bets. They’re going to place 50 or 100 bets for a fund, and every one of those funds should show a crazy return. A lot of times, an investor would rather go to zero than just get their money paid back, 1X or 2X. They want the thousand X.

Some founders might want [billions]. But some may just want to sell the company for $50 million because that’s a $10 million check for them. And that is life-changing money.

I think it’s important for founders to remember where VCs are coming from, and for founders to remember where they are coming from. A lot of the friction comes from differences in perspective on what we want the outcome to be.

b.: What else should founders know about VCs?

Neumann: Good founders will ask, “What can you do for me besides giving me money?” … I tell them there are a few things I can do for a founder: I can help you with strategic conversations. I can help you to vet C-level candidates. I can introduce you to more venture capitalists as you need them later in your company’s life. I can tell you what they’re going to want from your company.

But I can’t help you find customers. I can’t help you find employees, generally. I can’t help you find partnerships. I’m not going to read your code. I’m not going to be very good at vetting your product. I can’t help you with the operational things – and you don’t want me to help you with them. Those are so integral to your company that you have to be good at them. And if you can’t be better at them than I can, I don’t want to invest in your company.

I think there’s a misunderstanding of what my job is, as a financier, as opposed to somebody who is an operational part of your management. I want them to know that because I don’t want it to come back and haunt us later in life. There were some VCs who feel they have to tell the founder they can do more.

b.: What can founders and investors do to fix a relationship and continue working together if things have gotten off track?

Neumann: The best thing, obviously, is to not have the relationship go bad in the first place. If it goes bad, like any deep relationship, you have to sit down and have the hard conversations. Don’t try to fix it in the boardroom. You need to sit down with them, person to person.

And then, because it’s a group dynamic, if you have a problem with one board member or investor, that board member or investor has probably spoken to all the others. So, you need to fix the relationship with everybody else. It’s not usually confined to one person, which makes it a little bit harder.

Founders lose investors’ trust, because the investor thinks the founder is not looking out for the investors’ interest. And it is part of the founder’s job to also look out for the investors’ interest. They [also might] think, perhaps, the founder isn’t competent to solve the company’s problems because of something they’ve said or done.

Sometimes, the founders aren’t competent to solve the company’s problems. In that case maybe a different management is needed. But in a lot of cases, it is just because the founder approached the investor in the wrong way. You have to reassure investors that you know what you’re doing.

People start companies because they don’t want to be managed. They don’t want to work for somebody else. And now they have a relationship where they have to manage up.

b.: Liz, what should VCs know about founders?

I wish VCS would speak more frankly to founders. I have had contentious relationships with a few of my investors over the years. But what I have appreciated about those contentious relationships is they have told me exactly what they are feeling and exactly what they wanted to do.

One person once said to me, “If I’m going to stab you, it’s going to be in the front, not the back.” Which is a terrible thing to say, but it’s also completely true. It helps me to understand exactly the person I’m dealing with.

b.: Are there ways founders and investors can learn ways to work together and improve on their people skills?

Zalman: I’ve found I get to know investors just by spending a lot of time with them. With one of my investors, we used to walk around South Park in San Francisco, just around in a circle, again and again, with a coffee, just talking. We’d spend an hour talking every few months. It’s not in a room with other co-founders. I could create that personal relationship.

The cover of the book, purposefully, is Red Riding Hood and the wolf walking side by side, because they are on a journey together. And they have to do it together. One is not in front of the other.

b.: Let’s talk about the fundraise process a little. How can founders stand out?

Zalman: You need to create a narrative that is emotional. The narrative can strike fear in the heart of the investor, or it can be about a visionary future. Most founders forget that it’s not about the products. It’s not about the features. It’s not about their experience or where they worked previously. It’s not about the market size. It’s about getting the investor to believe that this idea is the right idea in order to solve some problem or address the future. And the majority of founders miss that and get stuck and get turned away. The investor is not as interested because they haven’t taken the time to craft the narrative.

Neumann: I’m in business. I invest in companies. Like any other business, I don’t want to be competing with a thousand other businesses doing the exact same thing. When a founder approaches me, I’m much happier when I feel like they are approaching me, and not a thousand people. Make me feel special, make it sound like you’re actually approaching me, and not that I’m just a commodity supplier of money.

b.: What else would you like investors or founders to know?

Neumann: The book has a provocative title, but in the end, we talk about whether we would invest in each other again. Would I invest in Liz again and would she take money from me and other investors again?

And the answer on both sides is, “Yes.” Even though we’re talking about inevitable problems, we both feel like it can work. And in some companies, it’s the best way to do things, to go ahead and raise money from someone else, and have a good relationship and work with them. We’re not saying you shouldn’t do it. We’re saying you need to go into it with open eyes.

This article first appeared in the b. Newsletter. Subscribe now!