MENU

Starting a Business

- Best Small Business Loans

- Best Business Internet Service

- Best Online Payroll Service

- Best Business Phone Systems

Our Top Picks

- OnPay Payroll Review

- ADP Payroll Review

- Ooma Office Review

- RingCentral Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Finance

- Best Accounting Software

- Best Merchant Services Providers

- Best Credit Card Processors

- Best Mobile Credit Card Processors

Our Top Picks

- Clover Review

- Merchant One Review

- QuickBooks Online Review

- Xero Accounting Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

- Accounting

- Finances

- Financial Solutions

- Funding

Explore More

Human Resources

- Best Human Resources Outsourcing Services

- Best Time and Attendance Software

- Best PEO Services

- Best Business Employee Retirement Plans

Our Top Picks

- Bambee Review

- Rippling HR Software Review

- TriNet Review

- Gusto Payroll Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

- Employees

- HR Solutions

- Hiring

- Managing

Explore More

Marketing and Sales

- Best Text Message Marketing Services

- Best CRM Software

- Best Email Marketing Services

- Best Website Builders

Our Top Picks

- Textedly Review

- Salesforce Review

- EZ Texting Review

- Textline Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Technology

- Best GPS Fleet Management Software

- Best POS Systems

- Best Employee Monitoring Software

- Best Document Management Software

Our Top Picks

- Verizon Connect Fleet GPS Review

- Zoom Review

- Samsara Review

- Zoho CRM Review

Our In-Depth Reviews

Business Basics

- 4 Simple Steps to Valuing Your Small Business

- How to Write a Business Growth Plan

- 12 Business Skills You Need to Master

- How to Start a One-Person Business

Our Top Picks

Job-seekers With Nonbinary Gender Pronouns on Their Resumes Are Less Likely To Be Contacted by Employers

Table of Contents

Today, approximately 1.2 million LGBTQ+ adults in the United States identify as nonbinary in terms of gender. Most of these individuals are under 30 years old, which means many are embarking on their professional careers. Among all LGBTQ+ professionals, workplace discrimination and bias are well-documented, but what about nonbinary people in particular?

Our three-phase study revealed bias against nonbinary people, both in the workplace and during the job search process:

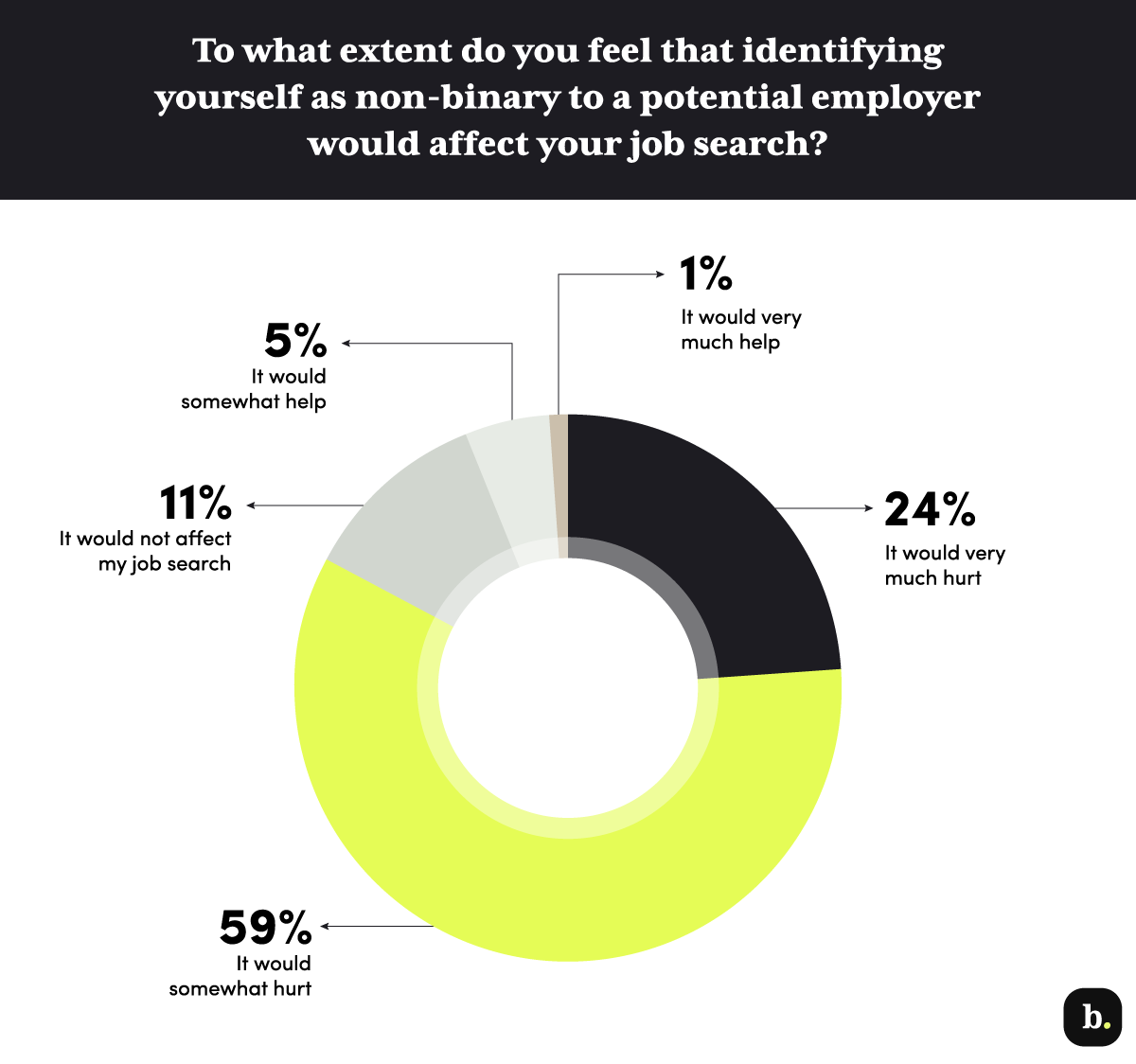

- First, we asked hundreds of nonbinary people how their gender identities impact their job searches and workplace experiences. More than 80 percent of nonbinary people believed that identifying as nonbinary would hurt their job search.

- Next, we sent two “phantom” resumes to 180 job postings. The resumes were identical, except the test resume included they/them pronouns, and the control did not. Though most companies were Equal Opportunity Employers, the test resume with pronouns received less interest and fewer interview invitations than the control resume.

- To find out why the resume with pronouns may have gotten less interest, we sought feedback directly from hiring managers. We found that these managers were also less likely to want to contact an applicant whose resume included “they/them” pronouns.

As major layoffs sweep through the U.S. workforce, these timely data show that nonbinary individuals may have a more difficult time finding new jobs. Despite increased awareness of the gender spectrum and the growing popularity of workplace bias training, employers still have more work to do to erase discrimination from their hiring processes and workplaces. [Read related article: The Hidden Ways Gender Bias Can Sabotage Recruitment]

| What does it mean to be nonbinary? |

|---|

| According to the Human Rights Campaign, a nonbinary person is someone “who does not identify exclusively as a man or a woman. Non-binary people may identify as being both a man and a woman, somewhere in between, or falling completely outside these categories. While many also identify as transgender, not all nonbinary people do.” |

Insights From Nonbinary People in the Workplace

Across the board, nonbinary folks worried that expressing their gender identity during a job search would harm their employment prospects. We spoke to over 400 nonbinary individuals about their experiences to understand how they perceived prejudice against them based on their gender identities. Most of the participants in our study preferred to use “they/them” pronouns.

The vast majority of people in our research believed that identifying as nonbinary would hurt their job search and limit their professional opportunities. Many felt they had to hide an essential part of their identities to simply earn a living. One 34-year-old full-time worker shared this sentiment with us. “I am in the nonbinary closet due to professional reasons,” they said. “I live in Florida, and coming out as nonbinary could cost me future job opportunities.”

On the other hand, some people in our study felt that disclosing their nonbinary identity during the hiring process could help them identify inclusive employers. “I am currently a student on a very accepting campus, so my on-campus jobs have not been affected by my gender identity. After I graduate, I think I should include my pronouns as early as possible so that I can see how potential employers react,” a 20-year-old student shared.

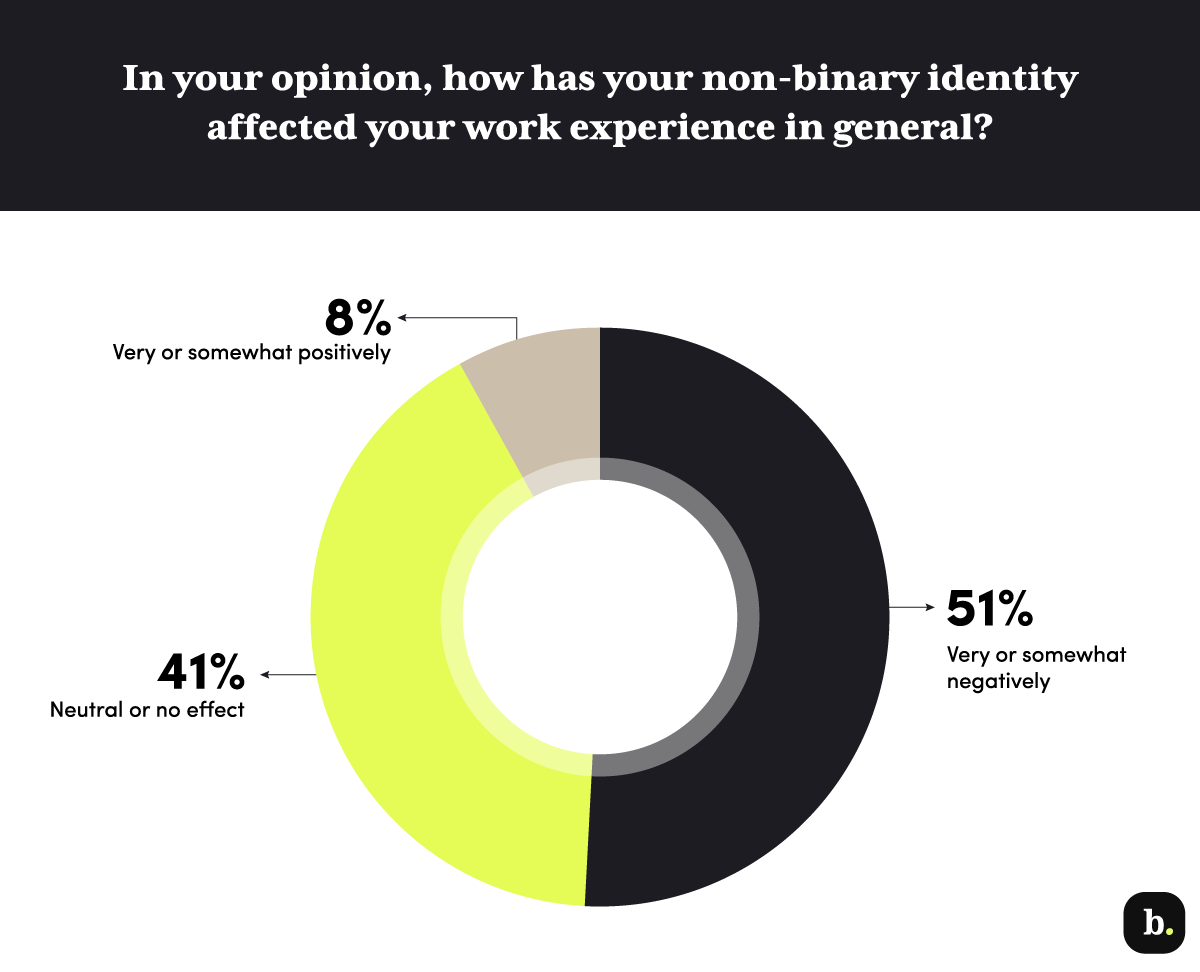

Beyond fears of prejudice during the hiring process, more than half of nonbinary people who have participated in the workforce reported having had negative experiences once hired.

Participants from the South were even more likely to feel this way than participants in other U.S. census regions. This region has historically espoused more conservative values and often makes headlines with anti-LGBTQ+ bills, such as North Carolina’s overturned “Bathroom Bill” and Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law.

“I have not experienced difficulty working as a nonbinary person in New York City, but I previously lived in South Carolina where it was more difficult… in South Carolina, I was told I had to stay closeted to succeed,” said one 25-year-old professional.

Forty-one percent of nonbinary people in the workforce reported that their nonbinary identity has had a neutral effect on their careers. This could be because many conceal their gender identity in the workplace to avoid both bias and outright violence. A young worker in Oregon said it felt unsafe to reveal this personal information to their colleagues: “People have complained about ‘the gay agenda’ to me. This is why I am hesitant to openly identify as nonbinary. It jeopardizes my personal safety to be out. I wish it didn’t,” they said.

In addition to regional differences, workers’ assigned sexes also played a part in how colleagues treated them. Non-binary workers who were assigned female at birth were likelier to report negative work experiences than their counterparts who were assigned male at birth. The Individuals who present as women or were socialized as girls during childhood may encounter dual discrimination because of their intersectional identities. The same can be said for nonbinary workers of color and those with disabilities.

A/B Resume Test Reveals Discrimination Against Nonbinary Workers

In an era of growing awareness of gender and sexual diversity, we wanted to discover if bias against nonbinary workers was still impacting companies’ hiring processes. To do this, we conducted a real-life experiment using two similar resumes. We modeled our research after a well-known study conducted by the University of Chicago and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2003, which evaluated racial bias in hiring practices.

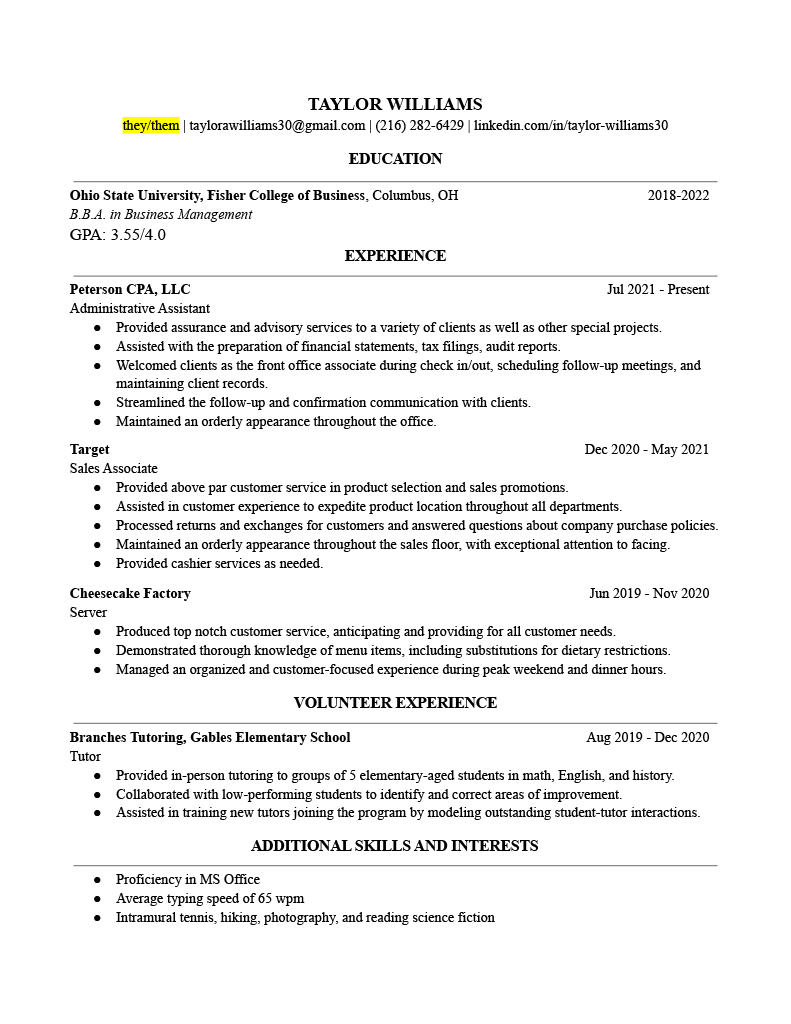

Instead of race, we tested whether or not the inclusion of gender-neutral pronouns impacts how employers perceive resumes. We sent the resumes of two phantom job seekers to 180 unique job postings that were explicitly open to entry-level candidates.

The test version of the resume, shown above, was identical to the control except for the presence of “they/them” gender pronouns beneath the name. This version performed worse in the experiment than the control resume without pronouns.

The resumes were mostly identical: both featured a gender-ambiguous name, “Taylor Williams.” The only difference between the test and control resumes was the presence of gender pronouns on the test version. The test resume included “they/them” pronouns under the name in the header (read our full methodology below).

These resumes aligned well with the jobs at hand: both phantom candidates were college graduates with qualifications matching the entry-level jobs they applied for. Despite this, the test resumes that included pronouns received eight percent less employer interest than the control resumes without pronouns.

We measured interest in each applicant based on whether the applicant received any request for additional information, such as a phone screen, interview request, or skills assessment. When analyzing the final results, we attributed a different value to each of these follow-up actions to appropriately weigh the level of interest in the candidate.

Our experiment revealed that the resume with nonbinary pronouns received less interest from employers and fewer requests for interviews or phone screens.

These results are especially worrisome because over 64 percent of the companies were Equal Opportunity Employers (EEO). EEO employers pledge not to discriminate against workers or applicants based on sex, gender, race, religion, ability, or age. In 2020, the Supreme Court declared that the law that bans sex discrimination also protects gay, lesbian, and transgender employees.

How might AI impact nonbinary applicants?

Today, many job applications submitted online are initially screened using artificial intelligence (AI) before being reviewed by HR professionals. AI screeners can determine if resumes and applications meet even the minimum criteria for job listings. In theory, something like pronouns should not factor into this assessment. AI programs should be neutral, but these systems are created and informed by humans, including their biases and preferences.

It is also a system that works very much in binaries – data sets and codes are, at their core, controlled series of numbers that do not leave room for human nuance. This is a problem that is becoming more and more apparent as more business functions rely on AI. Last year, Access Now, a digital rights organization, reported that AI filtering systems could undermine queer identity in this same way. AI hinges on predicting information about a person based on appearance, demographic data, and language, typecasting people into “boxes” and reducing them to binaries.

Study of Hiring Managers Confirms Bias Against Nonbinary Job Seekers

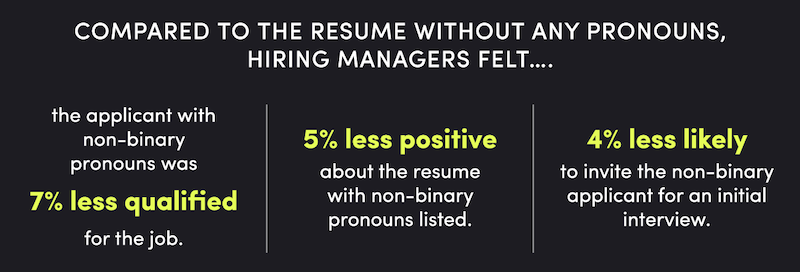

Our resume experiment revealed that employers favored applicants who did not directly disclose their gender identity. Still, it did not reveal why that may be, so we conducted an additional study to get qualitative feedback on these resumes. We first showed a customer service job description to about 850 workers with hiring responsibilities. Then we randomly showed them one version of the resume above – either with or without pronouns.

We found that hiring managers had fewer positive impressions of the resumes that included gender pronouns. Managers perceived these resumes less favorably, and overall, hiring managers were less likely to want to contact nonbinary candidates for initial interviews: 72 percent of managers said they’d contact the applicant on the control resume, but only 69 percent would want to interview the applicant whose resume contained “they/them” pronouns.

When we asked what, if anything, the applicants could improve about their resumes, several hiring managers revealed blatant biases and even bigotry against nonbinary job seekers. These professionals worked in a range of industries, including those that are often considered more progressive, such as entertainment and higher education:

- “This person seems like a decent fit on paper, though I am not interested in the drama that a person who thinks they are a ‘they/them’ brings with them.” – Man, age 57, agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industry

- “Take off the pronouns; I would trash the resume for that reason alone.” – Woman, age 59, manufacturing industry

- “I immediately balk at the supposed ‘gender neutral’ pronoun of ‘they/them.’ It doesn’t make sense when used like this and is, at its root, an attack on women.” – Man, age 32, arts, design, and entertainment industry

- “I am not a big fan of the pronouns at the top of the page. I am not saying that I hate them, but I feel that the pronoun listings, in general, are a little over the top.” – Man, age 32, retail industry

- “The pronouns are offputting and unnecessary. Get rid of the pronoun nonsense. You’re either a ‘he’ or a ‘she.’” – Man, age 36, college, university, and adult education industry

- “I would first take off the “they/them” pronoun reference. I find that personal pronouns are quite silly in a job situation. This is better reserved for social settings and not in a job setting.” – Man, age 50, hotel and food services industry

- “I would not include my pronouns such as ‘we/them’ as it may turn some potential employers away.” – Woman, age 37, college, university, and adult education industry

- “I might remove the person pronoun preference as older generations (and typically those hiring for a position) don’t get it.” – Woman, age 50, arts, design, and entertainment industry

The bias also existed in regions typically seen as more liberal. It existed equally amongst companies that were Equal Opportunity Employers and those that were not.

We also tracked how long each manager viewed the resumes. Respondents spent less time considering the resume that included pronouns than those who saw the control resume without pronouns. Even though not all hiring managers were not overt in their bias against nonbinary folks, this shows it was easier for many to make a decision about a candidate whose resume included pronouns.

How to Take Action Against Bias

In January 2023, more than 77,000 workers in the tech sector alone were laid off, and more cuts are expected through the first quarter of the year. Given the results of our experiment, it’s concerning that nonbinary workers who were laid off may have a harder time finding new employment – unless companies take decisive action to eradicate bias from their organizations.

Though building an equitable company culture takes time, intentionality, and effort (and often, expert guidance), there are a few steps employers can take to begin fostering the power of a diverse workforce today. We asked several experts to offer their advice on building inclusive. workplaces for workers of all genders, starting with their hiring processes.

In the hiring process:

- “Prior to [candidate] search, it may be a good idea to evaluate your search policies and/or practices to assure equitable participation in the search process… Consider adding members to your search committee from outside your department with expertise in your area or experiences that may add to the search’s success. Diverse committees also yield a more diverse pool of applicants.” – Dr. Michael Nguyen, educational psychologist at the University of Southern California

- “Use inclusive language for job descriptions: Ensure the language in the job description doesn’t deter potential employees from even applying. No need to be modest: include information about any diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts, policies, and how you are accessible to everyone.” – Dr. Nika White, DEI expert and author

- “Provide opportunities for self-identification: Interviews are stressful. Now, I invite you to imagine anticipating coming out during one. Yikes! Please, don’t put that pressure on nonbinary folks. Before the interview, give all interviewees the opportunity to provide their gender identity, pronouns, and preferred name. This next part is crucial – during the interview, use those pronouns. Practice makes perfect, and if you slip up, don’t make a big deal out of it. Correct yourself and continue with the interview.” – Sunday Helmerich, consultant at The Courage Collective

In the workplace:

- “In your company documents, use gender-neutral ‘they’ instead of ‘he or she’ or other gendered terms. If the company has a dress code, there should be one dress code for all genders, not one for men and one for women. All clothing options should be available to all employees. Your company’s health insurance options should include plans for men, women, and nonbinary. Likewise, health insurance options should include transgender medical care.” – Ruth B. Carter, attorney at law

- “If there is a gender fluid/trans/non-binary person in your office, remember and share that it is not their responsibility to be the spokesperson, educator, or the official expert on issues relating to gender identity. However, if they are open and willing to work with you to build a more inclusive workplace, they may be able to point you to binary gender concepts they’ve experienced and observed at work that you may have missed. By addressing them, you’re working in partnership to build a more inclusive workplace for all.” – Anna Dewar Gully, co-founder and co-CEO of Tidal Equality

- “Collect and analyze data to hold your company accountable to their diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives as well as help identify blind spots and encourage transparency.” – Dr. Michael Nguyen

- Share diversity data and celebrate progress: “One thing that really stood out to me was in a company all-hands meeting recently. I had never seen in my life a company share the percentage of LGBTQ+ employees along with other diversity metrics. I’d never felt that included or valued in a company before. It felt incredible to be seen.” – Tim Faherty, customer success manager at Compt

- Be an ally: “As a nonbinary employee, we are coming out and/or correcting pronoun usage on the daily. If you hear someone misgendered in a meeting, and have permission from that person to let others know they are nonbinary, take some of the burden off of them and speak up. A simple, ‘Hey, Sunday actually uses they/them pronouns’ in a meeting has done wonders to make me feel seen and supported by my colleagues.” – Sunday Helmerich

Despite increased legal protections and growing cultural representation of gender minorities, there is still much to be done to ensuring fair and equal treatment in the workplace. Our research confirmed the ongoing need to not only avoid wrong behaviors but also implement the right policies to eradicate bias in every industry and region.

Employers must critically assess their current hiring policies to identify and remove barriers that may exclude minorities. This may involve redirecting budgets to hire outside consultants or in-house DEI experts. Though creating equitable hiring practices is not an overnight process, it’s a necessary part of ensuring workplaces are inclusive and safe for professionals of all genders.

Methodology

Methodology

Non-binary individuals survey

We conducted an online survey of 409 U.S. adults who identified as nonbinary. All survey questions were multiple-choice.

Participants ranged in age from 18 to 60 with a median age of 24. Participants were residents of 45 different U.S. states plus the District of Columbia. Seventeen percent of the nonbinary individuals were assigned male at birth, 77 percent were assigned female at birth, and six percent chose not to disclose their assigned sex at birth.

A/B resume test with live applications

We developed identical resumes for two phantom job applicants. The test resumes versions of resumes included “they/them” pronouns in the header section beneath the name.

We submitted 90 applications for each applicant (a total of 180 applications) to remote jobs labeled as entry-level. The two applicants did not apply to the same job posting. All jobs were found on LinkedIn. Each applicant submitted 65 applications on the company site and 25 applications through the easy-apply method.

We checked the Equal Opportunity (EO) Employer status for all companies, and 64 percent (115) of the companies were confirmed as EO Employers. 58 applications from the nonbinary applicant and 57 for the control applicant were submitted to EO Employers. Because some applications required skills testing or other assessments, all applications were submitted by the same data scientist to avoid variations in methodology.

We limited our applications to those for which the applicants had a very high qualification match. Research shows that matching higher qualifications leads to fewer applications being needed before being offered an interview.

Our applicants were college graduates with a name and application that could pass as white and male. This was to avoid biases based on gender and ethnicity. We calculated an interest score for each job application based on probability of a job offer, qualification match rate, and interest shown by the company.

Interest score formula was calculated using this formula:

Base Value * Qualification Match Balance Weight * Interest Factor = Interest Score

BLS reports that applicants who submit 81 or more applications have a 20.36% probability of receiving a job offer. We used this as an initial value for both applicants. Because we applied to different jobs with different qualifications, our control applicant matched qualifications at a lower rate (87.38 percent match) than our nonbinary applicant (91.59 percent match), therefore we weighted down the nonbinary applicant interest responses (by 95.48 percent) to estimate their interest as if they matched qualifications at the same rate.

Interest from a company was assigned a value based on the interest shown from these sets of actions: an email or phone call that requested an interview, phone screen, assessment, or any additional steps on the part of the applicant.

Each type of interest was given a value as follows:

- Interest Factors:

- Interview = 1.81

- Phone screen = 1.4

- Assessment = 1.2

- Follow-up after initial interest = original interest value * 1.25

- No response of interest = 1.0

BLS reports that applicants who receive at least one interview have a 36.89 percent probability of getting a job offer. This was the basis for the 1.81 value given to the “interview” level of interest. This factor brings the initial base value of 20.36 up to 36.89.

Research on recruiter best practices shows that phone screens would lead 33-50 percent of applicants to the interview phase of the hiring process. This varies greatly between job listings and company procedures. It was simply a guideline. We generously assumed that 50 percent of applicants who receive a phone screen would proceed to the next phase. We assigned the median value (1.4) between no interest and interview level interest to the phone screen invitation level of interest.

Many companies using online hiring practices have automated screener requests for applicants that pass through an AI filter for qualification match. The assessments require no human interaction nor attention and simply mean that minimum qualifications were matched. Assessments then remove most of the applicants from proceeding to the next phase. This is the basis for the value of the “assessment” level of interest.

Additional interest value was given to any follow-up communication from an employer. If an employer contacted an applicant a second time, the interest factor of the first contact was multiplied by 1.25 to give added weight to the additional interest. The control applicant received nine percent more interest than our nonbinary applicant.

The statistical analysis shows little room for this difference in interest to be explained by random chance. The t-test was statistically significant with a p-value of: 0.00016. The effect size of the impact was calculated using Cohen’s d, which measures standardized mean difference. Cohen’s d = 0.55. This is a medium effect size.

Hiring managers A/B resume test

We showed 852 adult Americans with hiring responsibilities a description for a hypothetical entry-level position. We asked them to give feedback on a resume submitted for that role.

Our respondents ranged in age from 18-76, with a median age of 37. In our respondent pool, there were residents from each of the 50 states plus the District of Columbia. 54 percent of respondents were men, 43 percent were women, and three percent declined to identify.

Each respondent was randomly shown one of two resumes. The resumes were identical (including a gender-neutral name), except that the test resume included the pronouns “they/them” in the header below the name.

| Counts of respondents who saw each resume by gender | Total respondents | # men (including trans male/trans men) | # women (including trans female/trans women) | # another gender or preferred not to report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control resume | 461 | 219 | 161 | 11 |

| Test resume with pronouns | 391 | 239 | 209 | 13 |

The difference in the sample size of the two sets is due to the random assignment of the A/B resume. The dropoff rate for respondents was the same for both sets, therefore there was no indication of a difference between the rate of respondents discontinuing the survey after viewing their assigned A/B version.

The survey included two 7-point Likert scale answers (“Extremely low regard” to “Extremely high regard” and “Not at all likely” to “Extremely likely”). Two other questions called for open-text written responses. For the open-text, we performed sentiment analysis where a computer program analyzed the sentences to assess the polarity (positive, neutral, or negative sentiment) and magnitude (strength of sentiment) the respondents conveyed in their written responses. This analysis delivered a numeric value ranging from very negative to very positive for each open-text response. We also documented the length of time that each respondent took to fully complete the survey. We compared the average responses and survey completion times of the control resume (without pronouns) to the responses for the test resume (includes pronouns) and found the differences statistically significant.